The Flying Trees of Langholm

Sally Bavin, 16/06/2023

The Woodland Trust's Conservation Outcomes Manager, Saul Herbert, with an ancient alder and... can you spot the flying rowan? (Photo credit: Kate Lewthwaite)

You may have heard the saying "when pigs fly", but what about when trees fly?

The Woodland Trust's Conservation Outcomes and Evidence team pondered just that, as we were treated to a tour of some very special trees on a recent trip to the Langholm Initiative's Tarras Valley Nature Reserve, near Langholm in southern Scotland.

The Woodland Trust's Alan Crawford had joined us from the Scotland Outreach team. He led us over a babbling burn into a grove where some truly fascinating ecology was to be witnessed: the phenomenon of ‘Air trees’, ‘Cuckoo trees’, or Alan's preferred term ‘Flying trees’. This burn-side grove of ancient alder trees is more than first meets the eye. It is a living gallery, the perfect demonstration site for Alan to show and tell the whole story of the unlikely lives of flying trees.

Now, I had previously considered cuckoo trees an interesting example of an epiphyte, and have seen small rowan growing on ancient trees before. I had not thought too deeply about them, but assumed they probably didn't last very long, as surely they wouldn't have a stable footing, and would soon run out of whatever substrate they had managed to germinate in. Fortunately, Alan and fellow Woodland Trust colleague Alasdair Firth have been pondering on this much more deeply over the last couple of years, and were kind enough to share their knowledge and musings on these trees with us. Suitably inspired, we thought our network of Ancient Tree enthusiasts would surely appreciate this; so this blog is an abridged version of an article Alan wrote, with sketches by Alasdair Firth.

What is a flying tree?

A flying tree is a tree which spends most, if not all of its life elevated from ground level, by growing on the body of another tree. You can see a wide range of species as flying trees, as well as a wide range of species as host trees to these flying trees, but the most common association in Alan's experience is rowan trees growing within the crowns of alder trees. This is the combination we saw so perfectly illustrated in the ancient alder grove at Tarras Valley Nature Reserve. Nearly all the stages of a flying tree's life story were captured, like various snapshots in time.

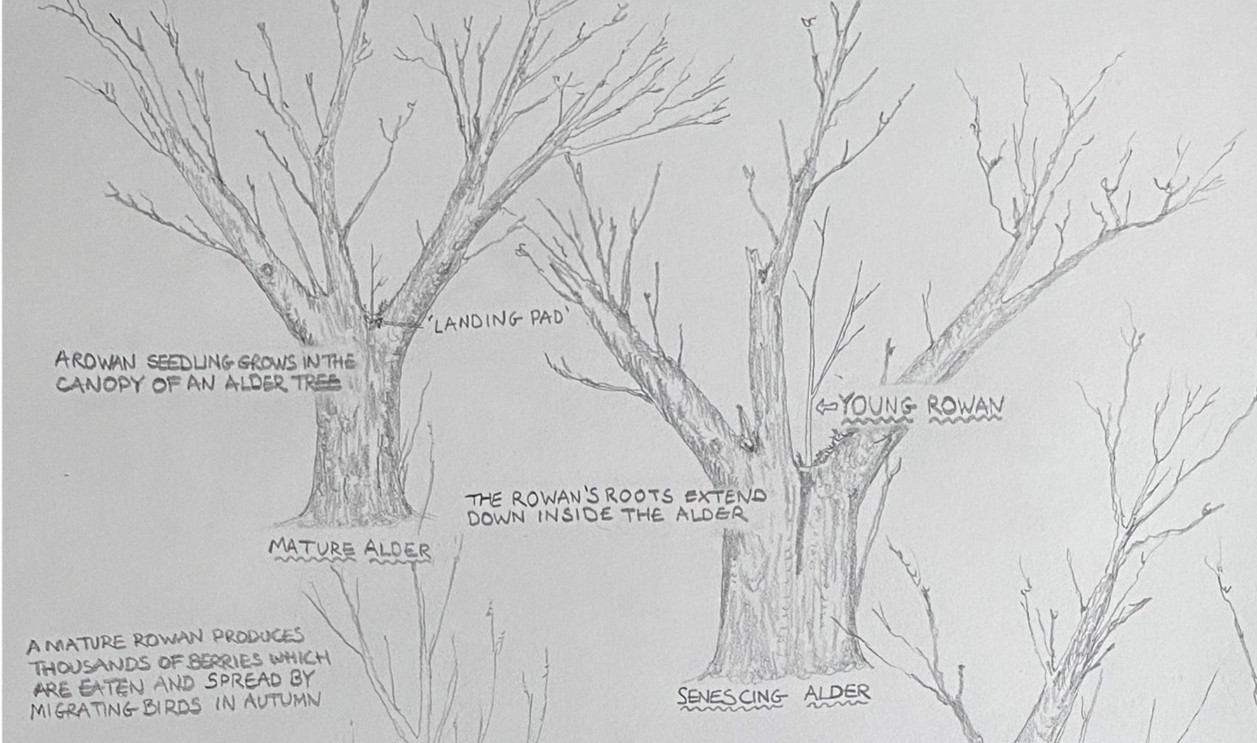

Sketch by Alasdair Firth showing the first two stages in the life of a flying rowan and its ancient alder host

How trees get wings

Why rowan trees are the most common flying trees, we presume is at least in part connected to the fact that their seeds are dispersed by birds after they have feasted on the rowan berries, flown off to the host tree to rest, and then let nature take its course. This is a particularly useful strategy for a palatable species such as rowan- way up out of the reach of hungry herbivores, the sapling is at a great advantage compared to its brethren whose seeds fell to the ground.

Why are alder the most common host trees?

This is less clear, and probably the result of the interaction of several factors.

The form of many alders; particularly pollarded or self-pollarded alders, but also many maiden trees, often split into several stems 2-3m up the main trunk and thus provide a platform for the birds to rest on or near, and importantly a platform from which the germinating seed can grow.

There must also be, something related to the rate at which alder wood decays, the way in which it decays (white rot, brown rot, soft rot), and that, of course, that will be related to the specific species of fungi that commonly associate with alders.

Perhaps it is also something to do with the fact that alder often live in damp/wet parts of the landscape, including riparian zones & floodplains; where a moisture rich environment would likely allow for greater moisture retention than in most other circumstances and therefore would speed up the process of decay of the alder stems. That decay process presumably allows the seed not only to germinate in ‘the stoor’ (the early decayed wood & other organic matter that combine to act as a seedbed) at these platforms, but also then allows the roots of the rowan to penetrate the decaying heartwood of the alders. Alan and Alasdair have looked for research on this but not turned up much. If anyone has info to share, please do get in touch!

Whatever it is, there must be something special about alder. With other host trees, the seed for the flying tree will sometimes germinate into a young seedling and then sapling. In particular circumstances they can grow into a large tree, but this is rare. When it does happen, the flying trees very rarely outlives the host tree, as often happens with rowan in alder, when they can grow into mature, veteran & even ancient trees in their own right.

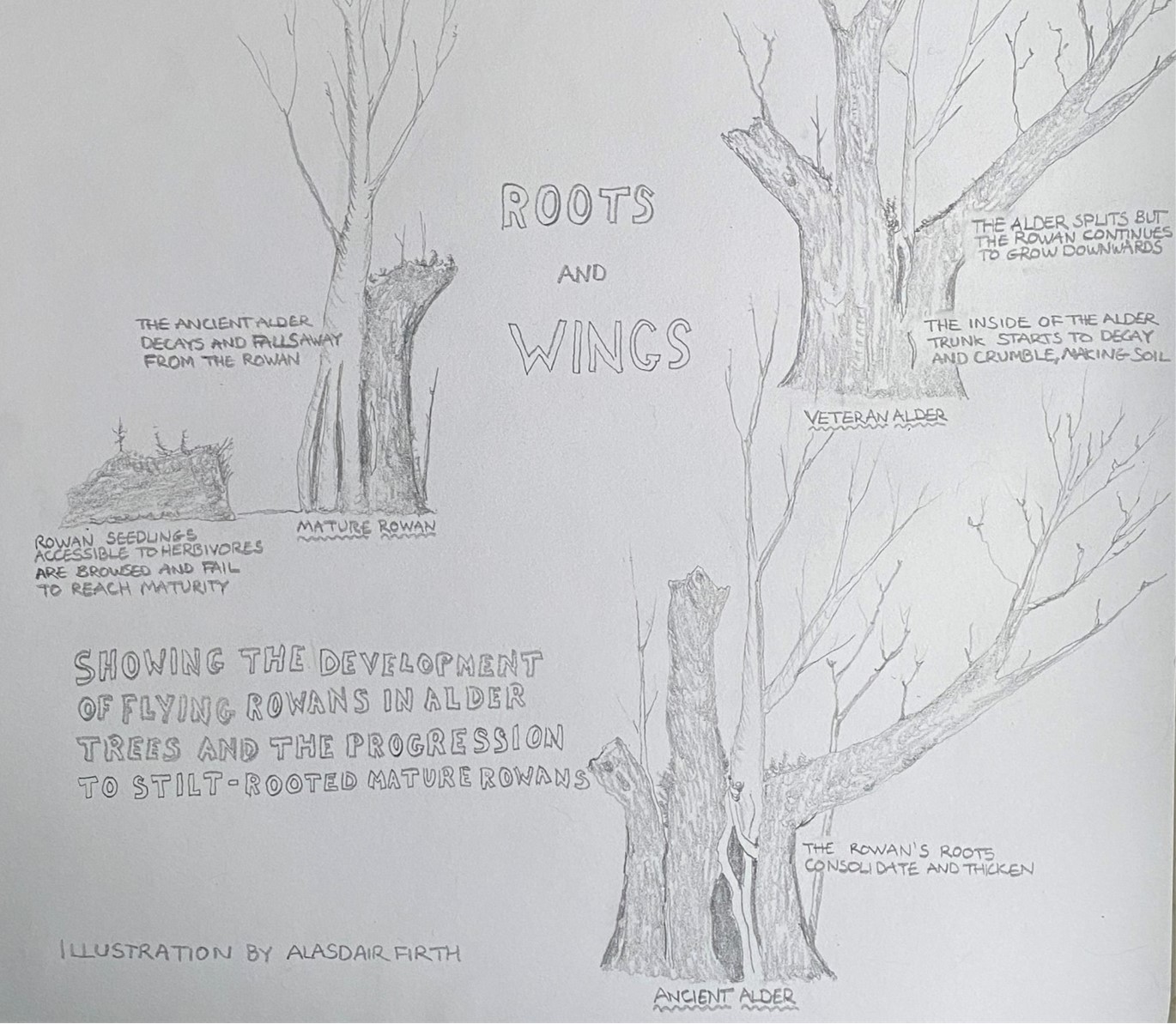

Sketch by Alasdair Firth showing the final three stages in the life of a flying rowan and its ancient alder host

Where to see flying rowans

There are some amazing woods and wood pastures in the north of Britain where flying rowans in the crowns of alders give us an insight into the functional aspects of this relationship. Places where trees (or tree partnerships) at different stages of the relationship grow in close proximity, so it is possible to build a picture of their life history. The Tarras Valley Nature Reserve is one such example, as well as Geltsdale in Cumbria, and the Woodland Trust's Glen Finglas.

Thanks to blackbirds, redwings, thrushes, fieldfares, and others, a rowan seeds itself in the crown of the alder. (Photo credit: Sally Bavin)

They can be quite high off the ground! (Photo credit: Sally Bavin)

The rowan seedling/sapling grows as the alder continues to mature. (Photo credit: Kate Lewthwaite)

the roots of the rowan begin to penetrate downwards inside the trunk of the alder. By the time the rowan is becoming mature, the alder is becoming a veteran tree with the roots of the rowan pushing through the hollowing stem of the veteran alder.(Photo credit: Sally Bavin)

As the alder gets older still and begins to decay further you begin to see the stilt roots of the rowans exposed. The alder now ancient, continues to decay until only faint traces of its existence remain in the form of thin strips of bark and some functioning physiological active tissue just beneath the bark at the outer edges of the tree. (Photo credit: Alan Crawford)

In time there is nothing remaining of the old alder and no hint that it was ever there except for the form of the remaining flying rowan that had seeded itself in the alder’s crown possibly hundreds of years previous. Now the rowan stands alone with only its stilt roots to hint at its fascinating story.

As time moves on, the stilt rooted (previously flying) rowans seem to respond in a number of different ways. Some will blow over in a wind, and those that remain alive will then become phoenix trees.

As the branches of the blown rowan grow into new ‘young’ trunks, and the fallen stem gets covered over by ground vegetation, it would be very easy to walk past such an ancient rowan with a fascinating story to tell and only see young ‘pole stage’ rowans.

We often describe ancient and veteran trees as ecosystems in their own right; and where alders and rowans associate like this, along with epiphytic ferns, mosses, lichens, decay fungi and saproxylic invertebrates; and where there are torn limbs, rot holes, water pockets among other features, it is clear why this is indeed an appropriate way to think of them. As Alan so eloquantly puts it: "The rowans bequeath their berries to this ecosystem; those berries fuel the wings of the birds that eat them; the roots of new rowan trees grow as a result; and the cycle continues."

A flying rowan that has outlived its alder host, blown over, but remained alive as a phoenix tree. An example of the later stage of the relationship between the two trees. Clearly the rowan is still going strong and can live for many more years. (Photo credit: Alan Crawford)

A final thought...

‘Hodding Carter the second’ (1907-1972), a progressive journalist and author from the deep south in the US, is famous for passing on an insightful comment that he’d heard - “A wise woman once said to me that there are only two lasting bequests, we can hope to give our children. One of these she said is roots, the other, wings”. I think she, & he are right . . . but when thinking about the nature of life on earth, not many things have both roots and wings - which I guess shows the challenge of supporting others to grow.

Huge thanks to Alan Crawford for sharing this content and allowing me to include it in this blog for the benefit of our Ancient Tree Inventory volunteers, and of course, thanks to Jenny Barlow and the team at Tarras Valley Nature reserve for hosting us for a fantastic and inspirational day. Finally, our enormous gratitude to the community of Langholm for securing the future of such a special site for nature. If you want to find out more about Tarras Valley Nature Reserve, you can visit their website Homepage - Tarras Valley Nature Reserve.